Our Blog

Ivan Franko – The Renaissance Mind of Ukrainian Literature and His Pursuit of Science & Social Justice

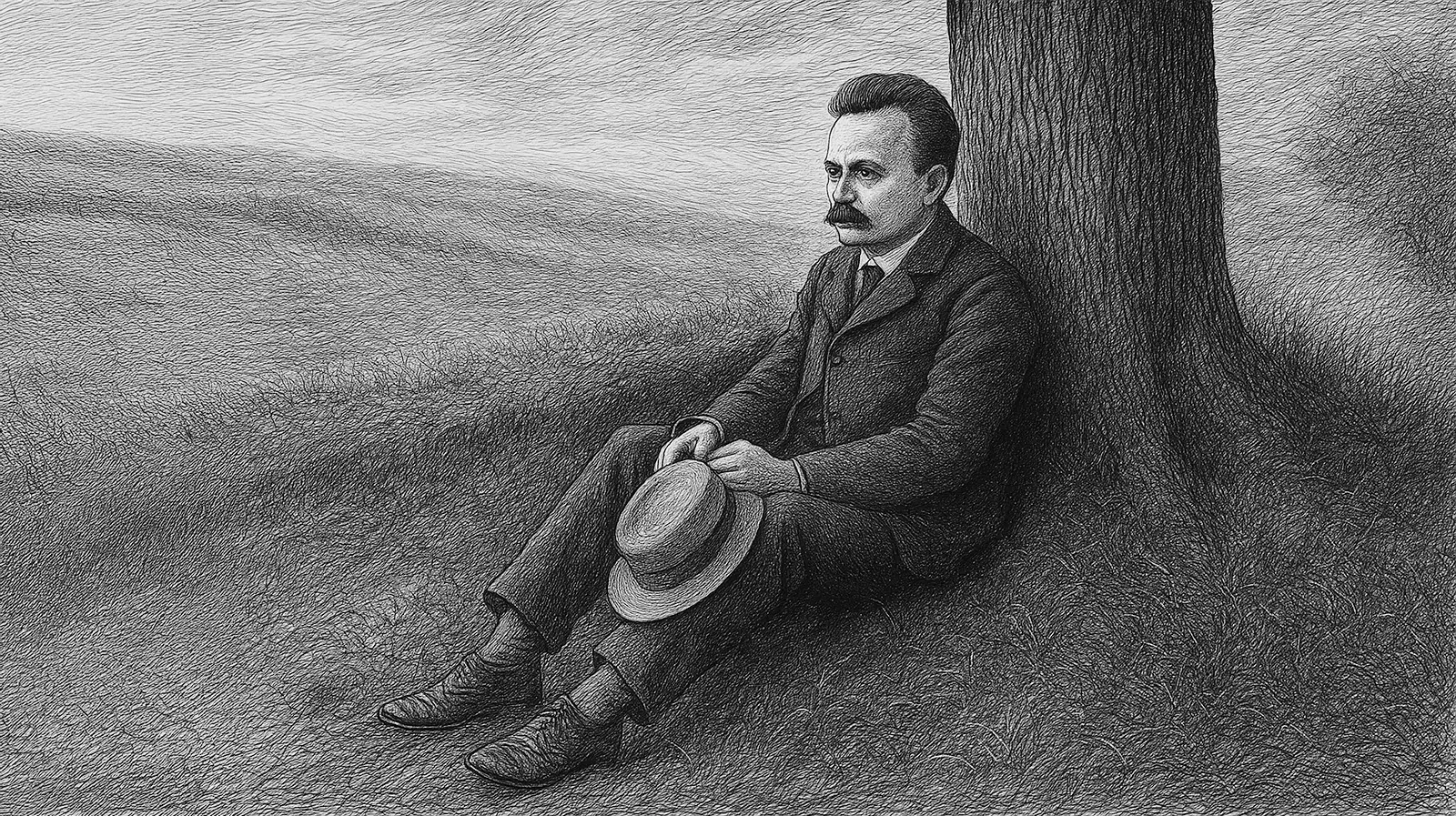

Introduction: A Colossus of Ukrainian Thought

Ivan Franko (1856–1916) stands as a colossus in Ukrainian culture, a true Renaissance mind whose prodigious intellect and unyielding spirit reshaped the intellectual landscape of his nation. More than just a poet, novelist, or dramatist, Franko was a polymath in the truest sense: an ethnographer unearthing ancient traditions, an economist dissecting societal structures, a translator opening windows to global thought, and a fervent political activist. His pen, fluent in over a dozen languages, danced across genres, producing an astonishing six thousand titles—from whimsical fairy tales that delighted children to incisive sociological monographs that challenged the status quo. At the heart of this monumental output lay an unwavering commitment to science, secular education, and social justice.

Franko’s genius was his ability to weave disparate threads into a cohesive vision: he seamlessly connected the oral epics of Galician folklore with the rigors of Darwinian biology, the elegance of classical poetics with the sharp edge of Marxist analysis, and the rustic life of his native Galicia with the sweeping currents of European modernity. This article endeavors to illuminate the multifaceted genius of Ivan Franko, situating his monumental writings at the vibrant intersection of literature, empirical inquiry, and the unceasing struggle for national and human rights. By tracing the contours of his remarkable life, exploring his major works, and assessing his enduring impact, we aim to reveal why Franko remains an indispensable touchstone for Ukraine’s cultural identity and its progressive, forward-looking thought.

Early Life & Education: Forging a Mind in Galicia

The seeds of Franko’s multifaceted genius were sown in the fertile soil of Nahuievychi, a Hutsul village nestled in Austrian-ruled Galicia. From his earliest days, he drank deeply from the wellspring of local culture, absorbing the haunting melodies of oral epics and the rich tapestry of Carpathian folklore that would later permeate his work. The untimely death of his blacksmith father cast a shadow, yet the boy’s undeniable spark of brilliance earned him scholarships, paving a path through the Lviv Gymnasium to the esteemed University of Lviv. There, his insatiable curiosity devoured Classical philology, Slavic linguistics, and the burgeoning natural sciences, laying a broad intellectual foundation.

But it was an arrest in 1877, a consequence of his burgeoning socialist activism, that proved a pivotal turning point. Confined within prison walls, Franko encountered the transformative ideas of Darwin, Spencer, and Marx. This period of enforced reflection became an intellectual crucible, forging his empirical understanding of the world with an unquenchable thirst for social reform, a potent combination that would define his life’s mission.

Literary Career: A Voice for a Nation

Franko burst onto the literary scene with his 1876 poetry collection, Ballads and Tales, a work that didn’t merely echo Ukrainian Romanticism but revitalized it, infusing it with stark realist detail and profound psychological depth. He was not content to remain within one genre; his pioneering spirit led him to craft Stolen Happiness (1893), a play that unflinchingly dissected the oppressive forces of patriarchy and the lingering shadows of serfdom, effectively birthing modern Ukrainian drama. This masterpiece laid bare the intimate struggles of individuals caught in the gears of societal expectation and injustice.

But his vision extended beyond his own creations. As the influential editor of Zoria (The Star) and co-founder of the prestigious Literary-Scientific Herald, Franko became a masterful curator, establishing a vibrant platform for emerging Ukrainian voices while simultaneously introducing his compatriots to the titans of European literature—from Goethe to Ibsen. Through these endeavors, he effectively globalized Ukrainian literature, thrusting it onto the world stage and fostering a sense of shared European cultural identity.

Explorations in Science & Philosophy: The Empirical Poet

For Franko, literature was not a realm separate from empirical inquiry but an extension of it—a laboratory for understanding the human condition. His groundbreaking essay, “On the Scientific Study of Literature,” argued passionately for a comparative, data-driven approach, decades before such methodologies became commonplace in literary theory. His mind, alight with the revelations of evolutionary theory, drove him to share this knowledge widely. He penned accessible popular science articles, lucidly explaining the complexities of geology and biology to peasant readers, empowering them with understanding and critical thought. His translation of Büchner’s Force and Matter into Ukrainian was another testament to this commitment to democratizing knowledge.

In the field of ethnography, Franko meticulously catalogued the ancient rituals and customs of the Hutsul people, his childhood community. He possessed a unique ability to see beyond mere tradition, adeptly linking mythic motifs to their underlying sociobiological functions—a methodology that foreshadowed later developments in cultural anthropology and demonstrated his integrative approach to knowledge.

Major Works & Enduring Themes

Franko’s vast bibliography is rich with works that continue to resonate. Among his most celebrated are:

Zahar Berkut (1883)

This sweeping historical novel, set in the 13th-century Carpathian Mountains, is more than just an adventure; it’s a powerful celebration of communal democracy and resilience. Its vivid depiction of a highland community’s collective defense against the Mongol invasion became a stirring allegory for national self-determination and the power of unity in the face of oppression, a theme that remains deeply relevant.

Boa Constrictor (1884)

Considered one of Eastern Europe’s earliest psychological thrillers, this novella masterfully portrays financial greed as a predatory serpent, slowly crushing its victims. It’s a chilling exploration of how unchecked avarice can corrupt the human soul, skillfully melding stark realism with proto-Freudian insights into the darker recesses of the psyche.

Prison Poetry (1878–1895)

Forged in the fires of his imprisonments, Franko’s cycles of prison poetry are intensely personal yet universally resonant. These powerful verses, such as the iconic “Hymn to Labor,” ingeniously fuse pagan imagery, the resonant cadence of biblical scripture, and an unshakeable evolutionary optimism. They position creative, purposeful work not just as a means of survival, but as humanity’s sacred path to liberation and self-realization.

Literary Style & Innovation: A Master of Form and Language

Franko’s literary toolkit was as diverse as his intellectual pursuits, marked by several key innovations:

- Multigenre Mastery: He moved with breathtaking ease between the soaring heights of epic poetry, the intimate depths of lyric verse, the confrontational power of drama, the biting wit of satire, and the grounded immediacy of reportage.

- Language Fusion: His Ukrainian was a vibrant tapestry, where the solemn dignity of high-church Slavonic diction met the earthy authenticity of village idiom, creating a uniquely polyphonic and richly textured effect that captured the full spectrum of human experience.

- Scientific Metaphor: Drawing from his deep engagement with the natural sciences, he frequently employed metaphors from geology, botany, and even astrophysics to construct potent symbolic frameworks for his philosophical and social ideas.

- Cinematic Realism: His narrative techniques, often characterized by rapid scene cuts and insightful interior monologues, strikingly foreshadowed the innovations of modernist literature, offering readers a dynamic and psychologically immersive experience.

Influence & Legacy: A Beacon for Generations

The ripples of Ivan Franko’s influence spread far and wide, shaping generations to come. He personally mentored literary luminaries like Lesya Ukrainka and Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, nurturing the next wave of Ukrainian talent and fostering a spirit of intellectual courage. His scholarly work laid foundational stones for comparative Slavic studies, establishing rigorous methodologies and new avenues of inquiry. Across the globe, Western scholars have often hailed him as “Ukraine’s Goethe,” recognizing the immense breadth and profound depth of his contributions to world literature and thought.

Even modern scientists acknowledge his pioneering efforts in popularizing evolutionary ethics and scientific literacy among the general populace. Today, the prestigious Lviv National University proudly bears his name, a living tribute to his academic legacy. Monuments in his honor stand as silent witnesses to his impact, from Kyiv to Winnipeg, and his resonant phrase, “the world is built on hope and labor,” continues to echo powerfully within Ukraine’s vibrant civil society, a testament to his enduring relevance in times of struggle and aspiration.

Conclusion: The Enduring Spirit of Franko

Ivan Franko’s extraordinary life and work stand as a powerful testament to the integrated intellectual—a figure whose art, science, and unwavering social conscience were inextricably intertwined. He forged an enduring template for the engaged life of the mind, demonstrating that intellectual pursuit finds its highest calling in service to humanity. His vast oeuvre serves as a compelling reminder that literature possesses the power to interrogate the natural world with the same rigor it applies to indicting injustice, and that beauty can be a weapon in the fight for truth.

Ultimately, Franko teaches us that the relentless quest for truth is, and must always be, inseparable from the unwavering defense of human dignity. He remains not just a historical figure, but a guiding light—a “Moses” for his people, as he was often called—inspiring all who believe in the transformative power of knowledge, compassion, and unwavering perseverance in the pursuit of a more just and enlightened world.

Related articles

Latest articles

Activism & Social Justice: The People’s Advocate

Franko’s pursuit of knowledge was inextricably linked to his fervent fight for human dignity and social equity. A co-founder of the Ukrainian Radical Party in 1890, he became a tireless and vocal advocate for systemic change. He campaigned relentlessly for universal suffrage, equitable land reform, and fundamental workers’ rights, even taking his impassioned arguments to the floor of the Habsburg parliament. His searing journalism unflinchingly exposed the grim realities of sweatshop labor and the pervasive exploitation by clerical and state authorities, giving voice to the voiceless.

Pamphlets like What Is Progress? translated complex egalitarian economic theories into language accessible to the common person, arming them with ideas. While he remained critical of dogmatic Marxism, Franko powerfully framed the class struggle not merely as an economic inevitability but as a profound moral imperative, deeply rooted in both Christian ethics and the tenets of humanist science. His activism was not without personal cost, leading to further arrests and persecution, yet his resolve to champion the oppressed never wavered.