Our Blog

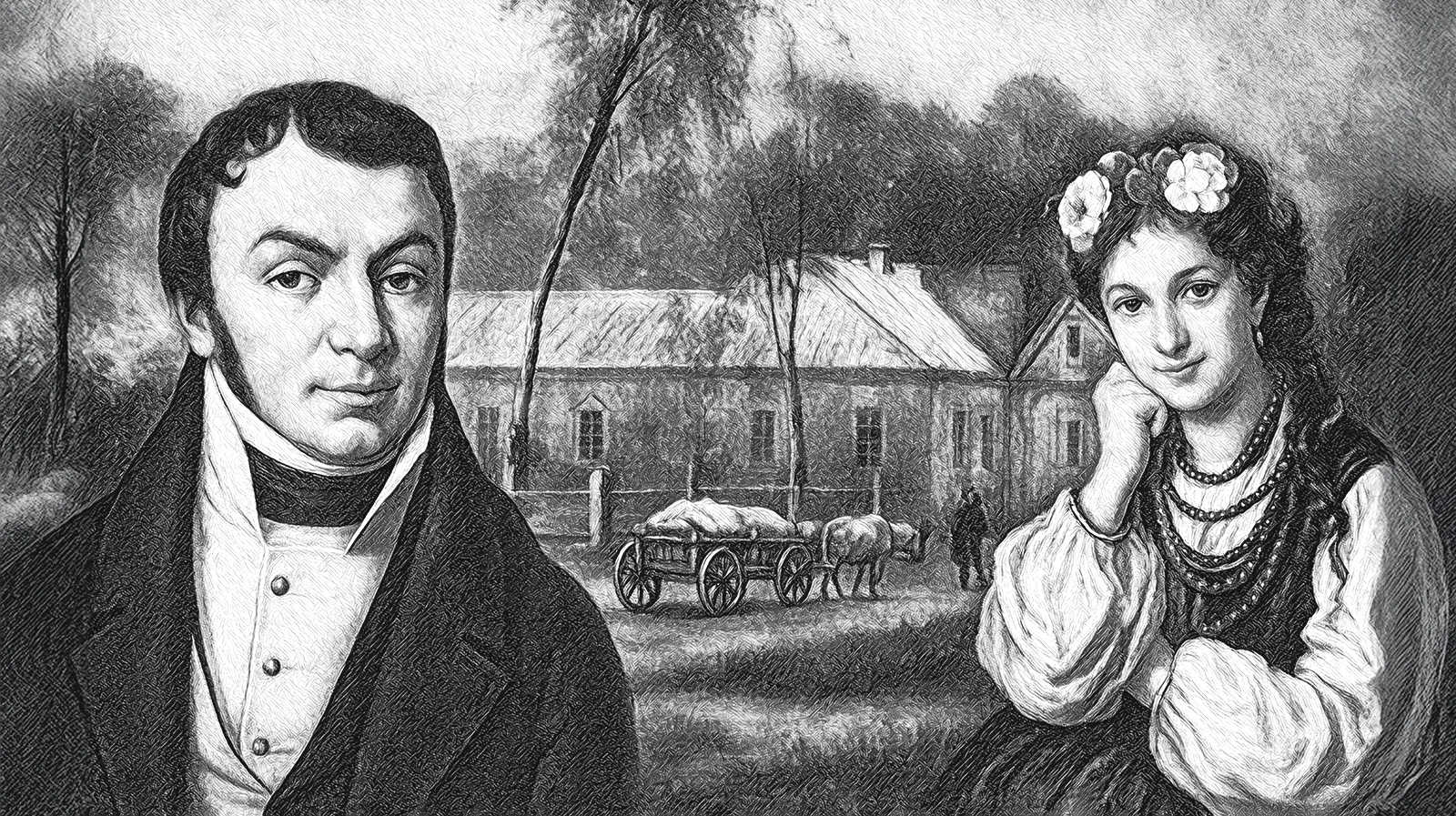

Hryhoriy Kvitka‑ Osnovyanenko – Founding Father of Ukrainian Prose and Architect of National Identity

Introduction: The Dawn of Ukrainian Prose

Hryhoriy Kvitka-Osnovyanenko (1778–1843) emerges from Ukrainian literary history as a foundational architect. Indeed, he is widely revered as the visionary who first sculpted Ukrainian prose into a vessel capable of carrying the nation’s soul. During an era of cultural suppression by the Russian Empire, Kvitka-Osnovyanenko made a bold choice. He championed the vernacular, the everyday speech of the people, transforming it into a powerful artistic medium. Furthermore, through his captivating fiction and drama, he lovingly elevated the simple dignity of folk life. In doing so, he began to encode an embryonic vision of Ukrainian national identity.

His stories skillfully blended heartfelt comedy with astute social commentary. They captured the authentic rhythms of village speech and explored the moral dilemmas of ordinary people. Consequently, Kvitka-Osnovyanenko laid a crucial literary cornerstone. Later titans, such as Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Nechuy-Levytskyi, would build upon this foundation. This article explores Kvitka’s life and cultural context. It also examines his major works, thematic concerns, and lasting impact on Ukrainian and world literature.

Early Life & Formative Influences: Roots in Kharkiv Soil

Hryhoriy Kvitka-Osnovyanenko was born into a minor gentry family near Kharkiv. His formative years became a fertile ground where deep-rooted Ukrainian folk traditions intertwined with progressive Enlightenment ideals. For instance, Jesuit-influenced schooling introduced him to Western dramatic forms. Simultaneously, local fairs steeped him in oral storytelling and song. These dual influences would become hallmarks of his later work.

The late 18th century saw a burgeoning cultural awakening. This was sparked by earlier printing enterprises in Lviv and Kyiv, which offered models of written Ukrainian. However, tsarist edicts still banned most Ukrainian-language publications. Therefore, Kvitka’s decision to write in Ukrainian was simultaneously an artistic and political act, a courageous statement in a difficult time.

Literary Context & Cultural Backdrop: A Language Under Siege

Ukrainian letters at the turn of the 19th century navigated a transition. They moved from late Romanticism toward emerging realism. Influenced by European sentimentalism, early Ukrainian writers often emphasized folklore and the Cossack past. Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, however, bridged these modes. He skillfully melded emotive Romantic settings with the concrete detail of realist prose.

The wider political landscape was complex. Partitioned Polish-Lithuanian lands lay to the west, and centralizing Russian power dominated the east. This created a multilingual frontier. Here, questions of language and identity were inseparable from literature. Kvitka’s prose, therefore, served as a subtle form of anti-colonial resistance. It quietly asserted cultural sovereignty.

</section

Major Works & Genre Breakthroughs: Carving a New Literary Path

Kvitka-Osnovyanenko’s pen was prolific, and his works blazed new trails for Ukrainian literature:

“Marusya” (1834)

Marusya is often cited as the first Ukrainian sentimental novella. This work tells a simple love story. Yet, it also monumentalizes rural morals and local customs. Significantly, Marusya proved that Ukrainian could sustain nuanced psychological narrative. It was a declaration of linguistic and literary capability.

Social-Household Comedies: The Birth of a National Theater

Plays such as The Courtship at Honcharivka and The Shelmenko-Orderly were revolutionary. Kvitka-Osnovyanenko ingeniously fused folk humor with sharp critique of petty-bureaucratic corruption. These comedies laid groundwork for modern Ukrainian theater. They created a stage where Ukrainian life could be portrayed and celebrated.

Short-Story Cycles: Voices of the People

Stories like “The Village Madwoman” and “The Soldier from Apostolove” showcase Kvitka’s mastery of narrative voice. He switched between an ironic narrator, a folksy sage, and a compassionate realist. In these works, he brought the diverse voices of the Ukrainian people to life, capturing their spirit.

Key Themes & Motifs: Weaving the Fabric of a Nation

Through his varied works, Kvitka-Osnovyanenko explored themes that resonated deeply and retain relevance:

National Identity & Cultural Survival: The Quiet Defense

Kvitka’s characters often defend local customs, language, and Orthodox faith against imperial assimilation. Interestingly, his plotlines hinge on preserving dignity and tradition rather than grand military exploits. This signaled a people-centric nationalism. It was rooted in cultural resilience.

Social Justice & Anti-Colonial Satire: Laughter as Resistance

Through comedic exaggeration of corrupt officials, Kvitka exposed colonial hierarchies. At the same time, he championed peasant wisdom. His dialogue indicted serfdom and patriarchal abuses without overt revolutionary rhetoric. This subtle approach often evaded censorship yet still stirred debate.

Faith, Morality & Sentimentalism: The Compass of the Heart

Christian ethics underpin many plots; compassion, humility, and familial piety are extolled. Sentimental scenes—such as tears, prayers, and deathbeds—functioned as moral instruction. These moments aimed to cultivate empathy in both rural and urban audiences.

Stylistic Innovations: The Sound of Authentic Ukraine

Kvitka-Osnovyanenko’s unique literary voice showcased several groundbreaking stylistic innovations:

- Hybrid Language: He crafted a literary Ukrainian seasoned with Church Slavonic archaisms and colorful Kharkiv dialect. This created a vibrant and authentic feel.

- Frame Narration: “Storyteller” personas often mimicked the oral skaz technique. This invited readers into an intimate, fireside circle.

- Code-Switching Humor: Sudden Russian or Polish phrases cleverly mocked imperial pretensions. This was a subtle form of wit.

- Ethnographic Detail: Meticulous descriptions of clothing, food, and ritual foreshadowed modern realist ethnography. These details painted a vivid picture of Ukrainian life.

Legacy, Influence & Modern Relevance: An Enduring Voice

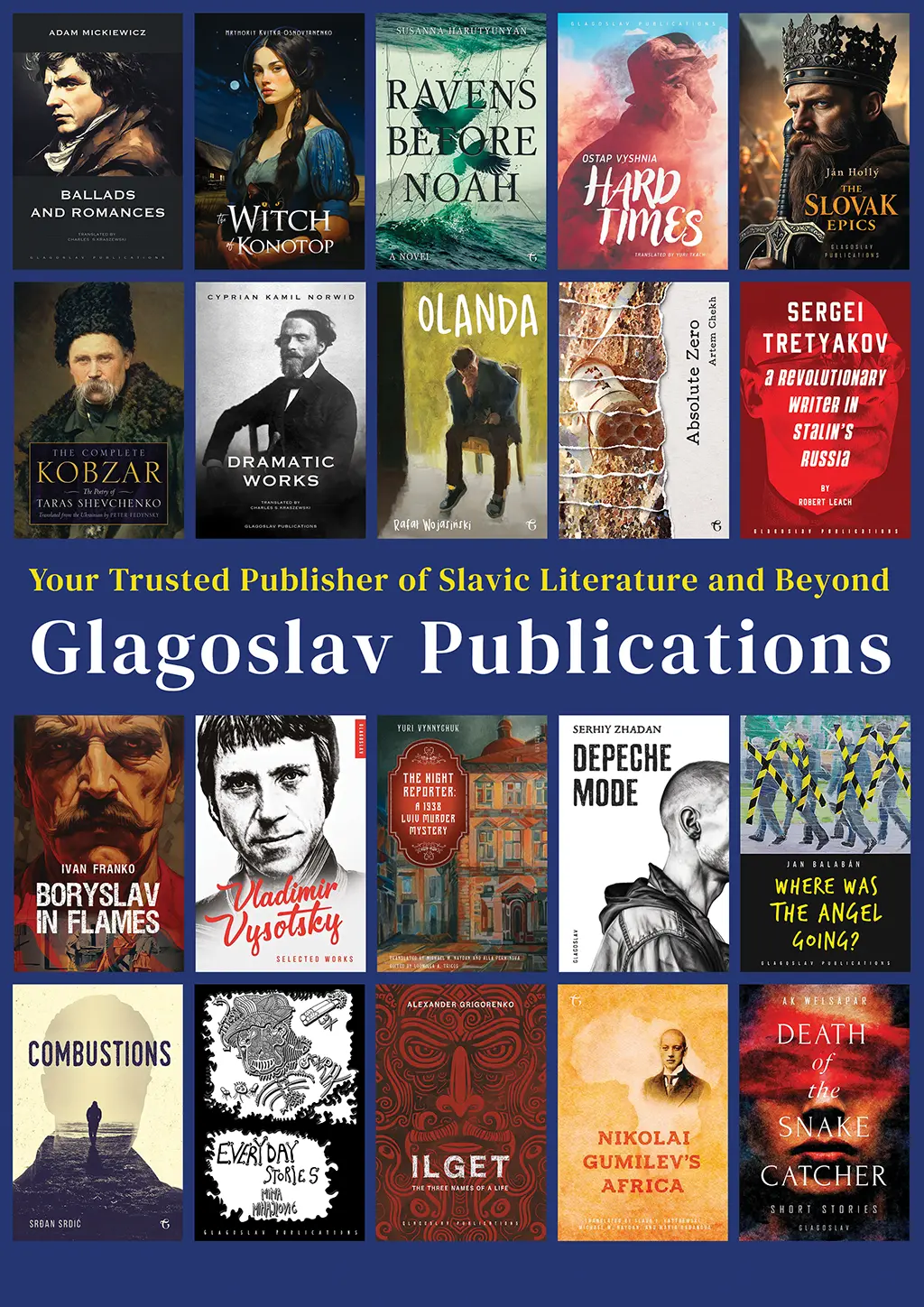

Kvitka’s validation of Ukrainian prose powerfully empowered his successors. For example, Shevchenko deepened socio-political critique. Nechuy-Levytskyi and Myrnyi expanded psychological realism. Furthermore, Lesya Ukrainka adapted folk comedy into European modernism. He was, in essence, a crucial starting point for much of 19th-century Ukrainian literature.

In today’s Ukraine, language again marks resistance. Consequently, Kvitka’s insistence on vernacular dignity resonates powerfully. His comedies are revived on post-Soviet stages, their humor still relevant. Moreover, his novellas appear in new translations. These speak to global conversations about decolonizing literature, affirming Ukraine’s rich heritage.

Conclusion: The Enduring Architect

Hryhoriy Kvitka-Osnovyanenko transformed everyday speech into art. He also elevated village life into the national narrative. By doing so, he established Ukrainian prose as a vehicle for cultural self-assertion. His blend of humor, realism, and moral vision continues to shape Ukrainian literary identity. Ultimately, Kvitka-Osnovyanenko offers a timeless model of how storytelling can nurture a nation’s soul.

Related articles

Latest articles